SUMMARY

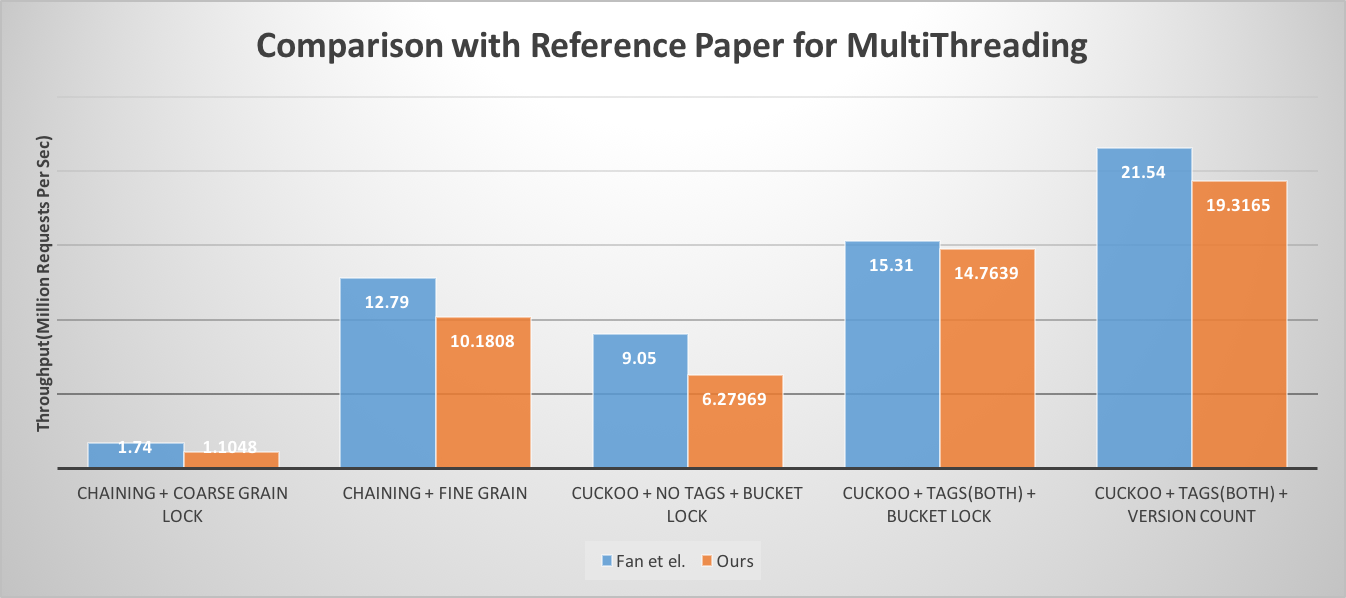

We implemented a concurrent in-memory hash table based on optimistic cuckoo hashing[1]. This hash table is optimized for high space efficiency and high read throughput. Therefore, it is best suited for read heavy workload with multiple readers and single writer use-cases. We have incorporated improvements mentioned in MemC3 by Fan et al[1], and we were able to achieve similar performance numbers (95% space efficiency and read lookup throughput of ~21 Million Ops per sec). We developed and tested our implementation on Latedays cluster (Intel Xeon CPU E5-2620).

BACKGROUND

Hash Table is a widely used data structure. In any efficient hashing scheme, collisions are frequent and chaining is the most common method to resolve the collisions. Chaining is efficient for insertions and deletions, however, lookup can be quite expensive as it might require traversal of the entire linked list of a bucket. In addition, locking, whether it’s coarse-grained or fine-grained, can add significant overhead to chanining in case of multi-threading. Even when fine-grained locking is used with chaining, obtaining locks is still a major overhead as it is highly likely that several distinct keys can map to the same bucket.

There are multiple applications like MemC3[1] which have have dominant read-only workload with rarely occurring writes. In these applications, to support multi-threading, locks are heavily used as writers can be present in the system (rare, but still possible). Hence, though most queries are reads, they get major performance hit due to overhead associated with locks.

The approach described in Fan et al.[1] tries to optimise for the common case, by removing all the mutexes and assuming that read-write conflict will rarely occur. It replaces mutexes with an optimistic locking scheme to resolve the conflicts. It also adds other optimisations to make lookups faster and more cache-friendly.

To implement optimistic hashing scheme, it uses cuckoo hashing - an advanced hashing scheme with high memory efficiency and O(1) expected insertion time and lookup. The basic idea of cuckoo hashing is to use two hash functions instead of one, thus providing each key two possible locations where it can reside. Cuckoo hashing can dynamically relocate existing keys and refine the table to make room for new keys during insertion[1].

Unfortunately, there are some fundamental limitations in making cuckoo hashing parallel. It does not support concurrent read/write access by default. Also, it requires multiple memory references for each insertion and lookup. The hashing scheme described in above mentioned paper supports concurrent access while still maintaining the high space efficiency of cuckoo hashing.

APPROACH

To implement concurrent hash table with high space efficiency and high read throughput, we added following features to basic cuckoo hashing, to overcome its limitations:

- Making hash table structure cache friendly by using tag

- Tag is a single byte summary of the key which improves cache locality during hash table operations.

- Boosts throughput by reducing cache misses and memory references.

- Optimistic Locking using Version Counter

- Maintains version counter which supports concurrent access by multiple readers and single writer.

- Improves throughput by avoiding locking overhead.

Hashing using chaining requires up to N dependent (non-parallelizable) memory references for a bucket having N keys. A single lookup in a naive cuckoo hashing requires two parallel bucket reads followed by up to 2N parallel memory references if each bucket has N keys. However, in the above described scheme, each lookup requires only two parallel cacheline reads followed by upto one memory reference on average. This approach gives a significant performance edge to read-heavy workloads.

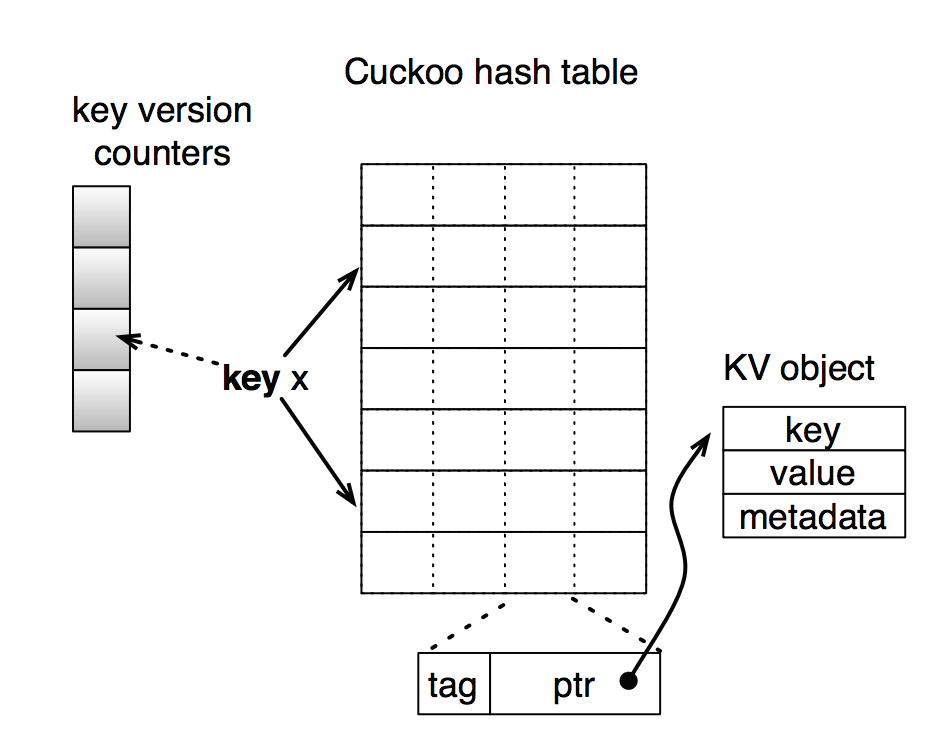

Hash table structure

Our hashtable’s unit structure is a slot. Each slot contains a tag, short summary of the key and a pointer to key value object. Each bucket is 4-way set associative and hashtable is an array of these buckets. Each key is mapped to two random buckets of the hashtable. There is an array for key version ounters, which is used for optimistic locking.

Following are the steps for non-tag based hash table operations:

Lookup:

- As each key is mapped to two buckets, lookup checks all 8 possible slots for the key.

- And for each slot, it makes a memory reference and then it is compared with given key.

Insert:

- For a key x, get two buckets b1 and b2. If any of the slot is empty in these buckets, simply insert the key in that slot.

- If no empty slot is found, then it randomly selects a victim slot out of these 8 slots.

- Displaces the victim slot’s key to its alternate bucket.

- If an empty slot is found in that bucket, simply insert the key and displacement stops.

- Otherwise, repeat this procedure until we find an empty slot or until maximum no. of displacements are performed. The entire path of displacements is known as cuckoo path.

- Though it may execute a sequence of displacements, the expected insertion time of cuckoo hashing is O(1) [5].

Cache Friendly Operations using Tag

In previous approach, while checking all 8 candidate slots for a lookup, we need to make 8 memory dereferences to compare the keys. For insert, while performing displacements along a cuckoo path, we need to access entire key to get the alternate bucket, as the buckets are determined based on hash of keys.

There is an alternative cache friendly approach using tag, where we store tag, one byte hash of the key, in hashtable. Now each slot has 1-byte tag + 8-byte pointer and each bucket has 4 slots. Therefore, each bucket can still fit in a single cache line of 64 bytes.

Now lookups and inserts work in following manner.

Lookup:

- Get the buckets b1 and b2 by hashing the key.

- Calculate the tag of the key.

- Compare tags stored in these 8 slots with this calculated tag.

- Compare the key by making memory dereference only if tag matches. (Since tag collision is still possible)

Insert:

- Get bucket b1 and b2 for key.

- Try to find an empty slot among these 8 slots

- If none found, select a victim slot, start displacements until an empty slot is found.

In this approach of insertion, next bucket is calculated based on tag stored in the victim slot. This saves us one pointer dereference every time we find next victim slot, as compared to previous approach where finding next bucket requires a memory dereference for accessing key. As a result, insert operations never have to retrieve keys.

In this method, buckets b1 and b2 for any key x can be computed as below:

b1 = HASH(x)

b2 = b1 ⊕ HASH(tag)

Hence, given a bucket b and tag, alternate bucket for a key can be computed as:

b’ = b ⊕ HASH(tag)

Concurrent Access:

There are mainly three issues due to concurrent access that we need to address.

- Deadlock risk due to multiple writers (during displacements along the cuckoo path)

- Avoided by allowing only single writer at a time

- False misses:

- Suppose during insert for key x, no empty slot was found. A victim slot y was selected.

- Now we get alternate bucket z for y.

- We replace y with x and then z with y.

- But, after replacing y with x, and before putting y in z, key y was not present in the hashtable, hence giving a false miss to a lookup for y.

- This problem is solved by separating search and displacement phase.

- First we get the entire cuckoo path without performing any replacements.

- In second phase, we start atomic swaps from the end.

- This way, all keys in the cuckoo path are always present in the hashtable and false misses can be avoided.

- Optimistic Locking:

- There is still a possibility of race condition between readers and and a single writer (writer’s displacement phase can move the keys being read by a reader).

- To avoid using locks, we use version counters. Each key maps to a specific index in the version counter array. More than one keys can map to same index in the version counter array.

- Before insert modifies a key location, it atomically increments the counter in the array for that key. We use __sync_fetch_and_add() for this purpose.

- Once insert is done with the modification, it again increments the counter atomically.

- Lookup checks if version counter at the index for the key is even or odd.

- If it is odd, then insert is in the middle of the modification and hence lookup should stall.

- If its even, then lookup can continue.

- Before returning, we check if the version counter has changed since when we started reading the value in lookup.

- If yes, then we retry the lookup because this key has been modified by an insert.

- If not, then the lookup was successful.

RESULTS

We analyzed how various optimization techniques contribute to the high throughput and space efficiency of our hash table’s implementation. We compared its performance with various other hash tables’ implementations, which selects different tradeoff points in design space. Finally, we compared our implementation’s performance with the performance results mentioned in reference paper [1].

Platform

We developed and tested our implementation on Latedays cluster, which consists of Intel Xeon CPU E5-2620 v3 @ 2.40GHz, with 15 MB cache. This configuration is quite similar to the ones which were used for experiments in reference paper, which had Intel Xeon L5640 @ 2.27GHz, with 12 MB cache.

Testing Framework

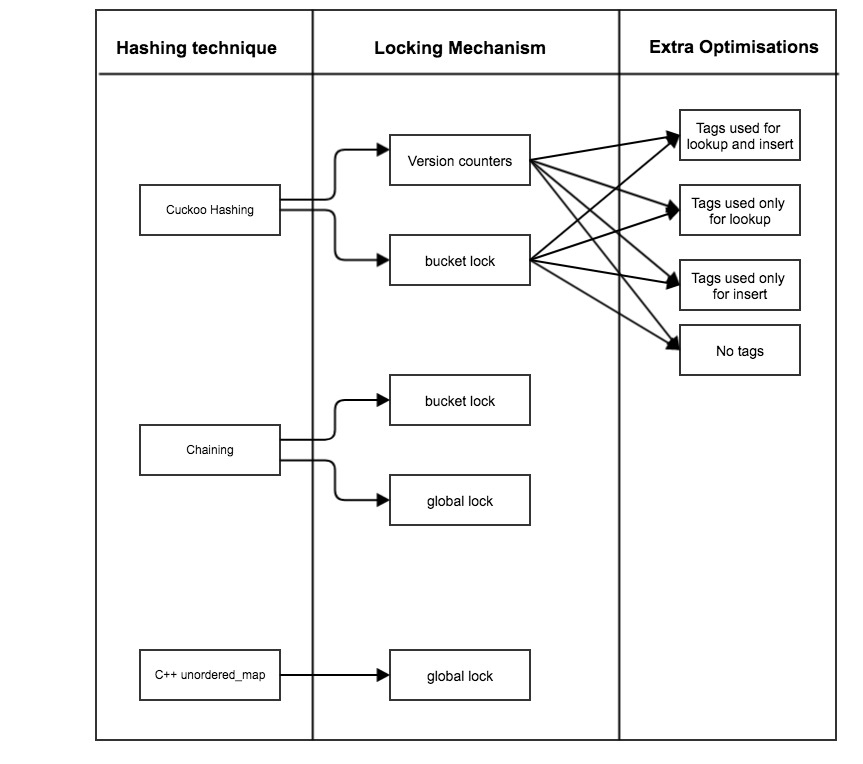

Hashing schemes

Following combinations of hashing schemes were tested to get the different comparisons.

Workload

All combinations given above were tested with mainly three types of workloads.

1) Read-write interleaved with low load factor

2) Read-heavy with low load factor

3) Read-heavy with high load factor

Here, the load factor determines current occupany of the hashtable.

Size of the Hash table size = ~ 4 MB keys

Size of version-counter array for cuckoo hash = 8 KB

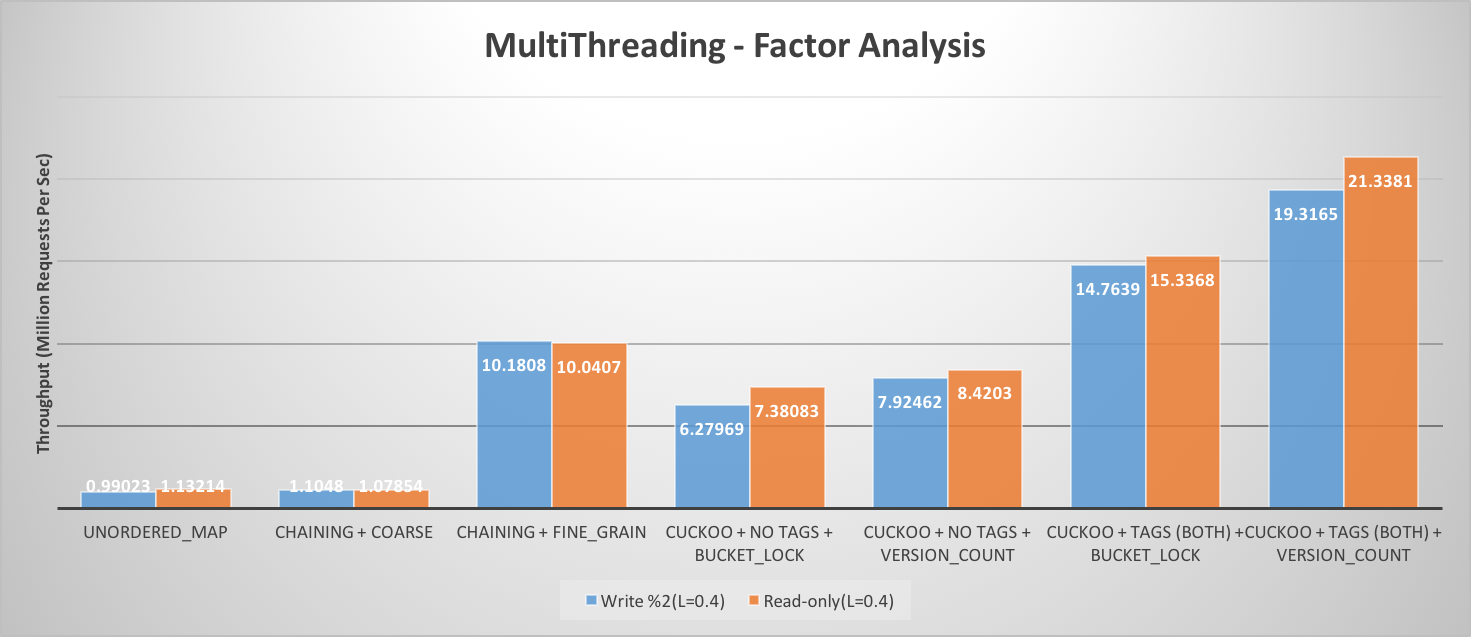

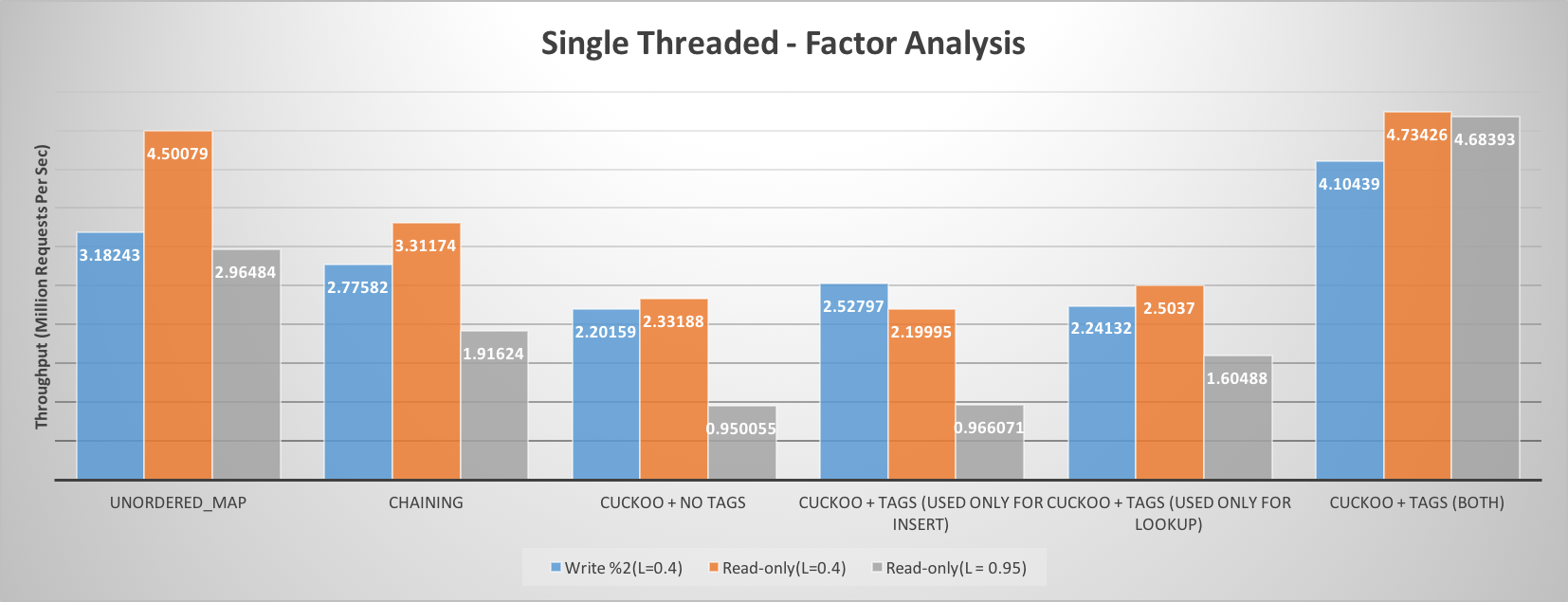

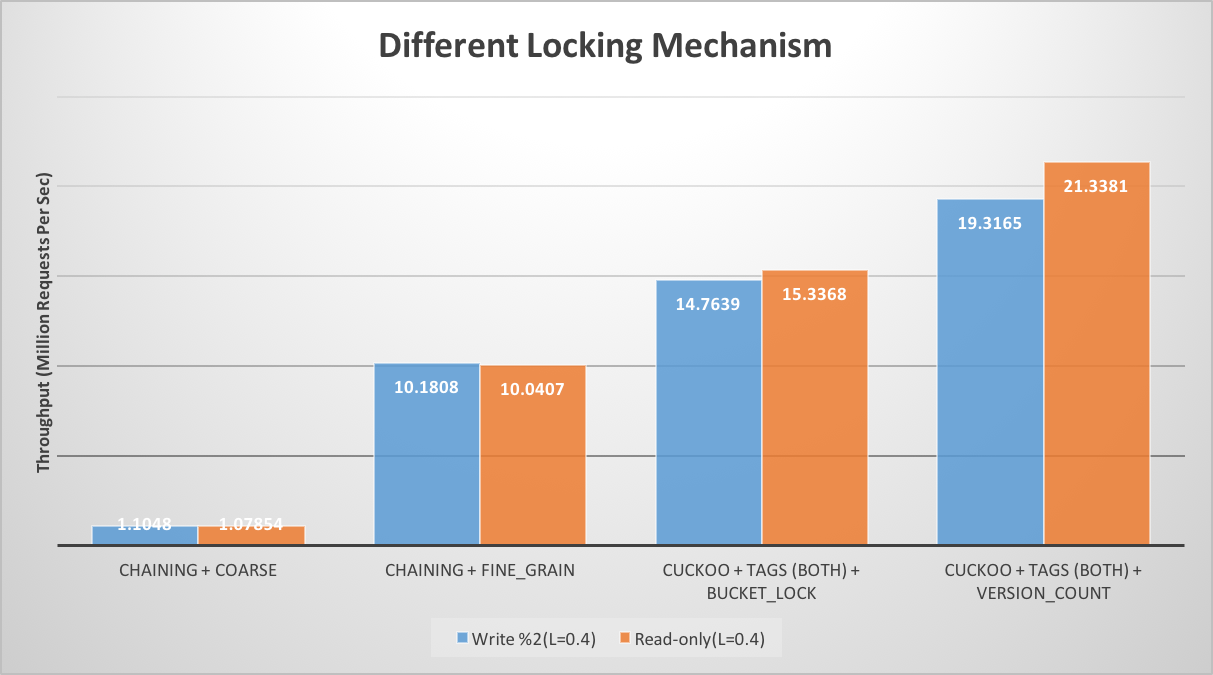

Overall Comparison of Various Hash Table Approaches

We analyzed various hash table approaches both for single threaded and multi-threaded scenarios. Following figures demonstrate how various factors contribute towards the read throughput performance. We concluded cuckoo hash table with optimistic locking mechanism and tag byte gives the best performance for read heavy workloads. In subsequent sections we will analyze each of performance optimizations in depth.

Optimistic Locking Mechanism

We implemented two kinds of locking mechanism for cuckoo hash table. One is per bucket locking, whereas other is optimistic locking based on version counter. Optimistic locking performs significantly better than bucket based locking. It also beats chaining based hash table with coarse grain as well as fine grain locking by a big margin. As in optimistic locking, there is no need to take any kind of locks, it allows multiple concurrent reads and reduces significant overhead associated with locking. As this hashing scheme is designed for read heavy workload, the overhead associated with read retries during read-write conflict, doesn’t hurt overall throughput much.

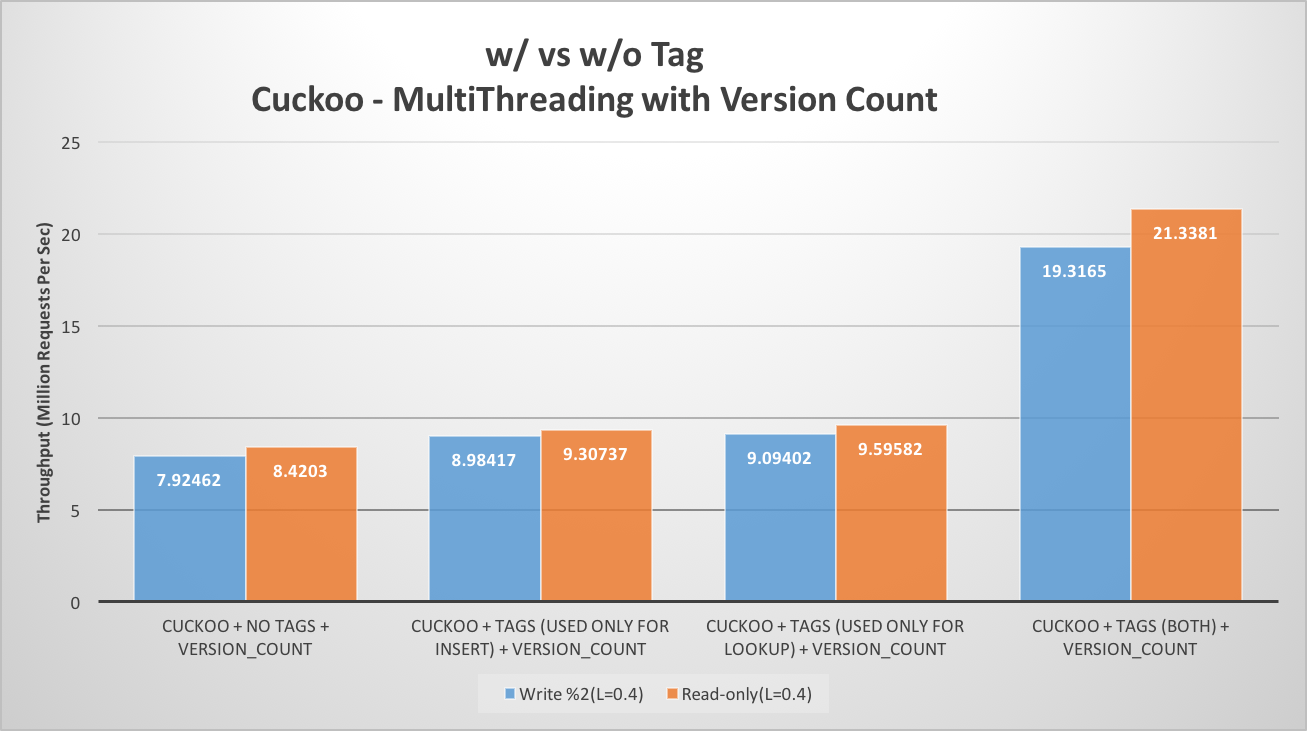

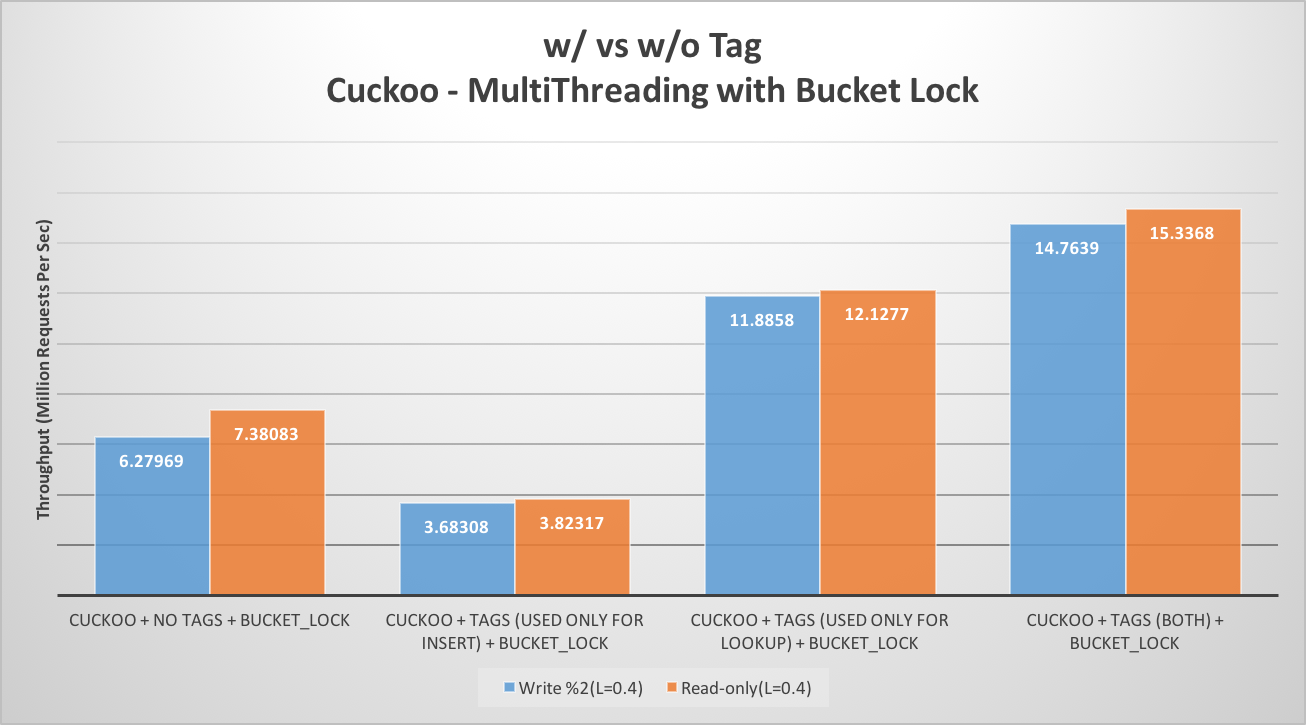

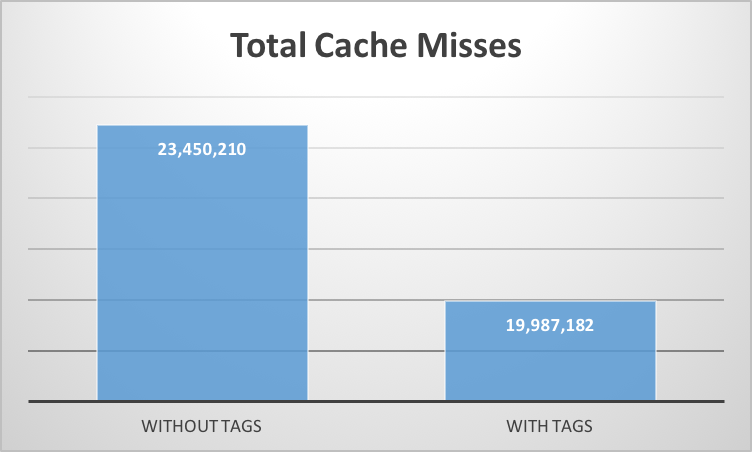

Cache Locality Improvement Using Tag

Introduction of tag significantly boosts the throughput of the hash table, both for read only as well as read-write work load, as illustrated in the following figure. The main reason for this boost is cache locality. During lookup, it needs to check for the key in all the slots of both buckets. First of all, the 1-byte tag eliminates the need for fetching complete variable length key from memory for most slot checks, except when there is a tag hit. As the tag size is only 1 byte, as compared to variable length key, it makes sure that complete bucket fits in a single cache line. Similarly, it helps during path search phase of insertion. Using the tag which resides in cache significantly speeds up the insertion instead of using complete key (which may reside in memory) for finding the next bucket.

Following cache-miss statistics were obtained for an implementation of optimistic cuckoo hashing with and without tags. Cache misses were measures using perf tool

Space Efficiency

Our cuckoo hash table was able to achieve as high occupancy as ~95%, without compromising on O(1) worst case lookup. Each key can be mapped to 2 buckets, each bucket having 4 slots. Cuckoo path length of 500 was used as an upper bound on no. of consecutive displacements in search for an empty slot for insert, before declaring it as unsuccessful insert.

Also, as compared to chaining based hash table, it has lower overhead for bookkeeping information. Hash table with chaining needs to store 4 or 8-bytes pointer, based on machine type, to the next item in the bucket. On the other hand, cuckoo hash table just needs to store 1-byte tag for faster lookup and inserts.

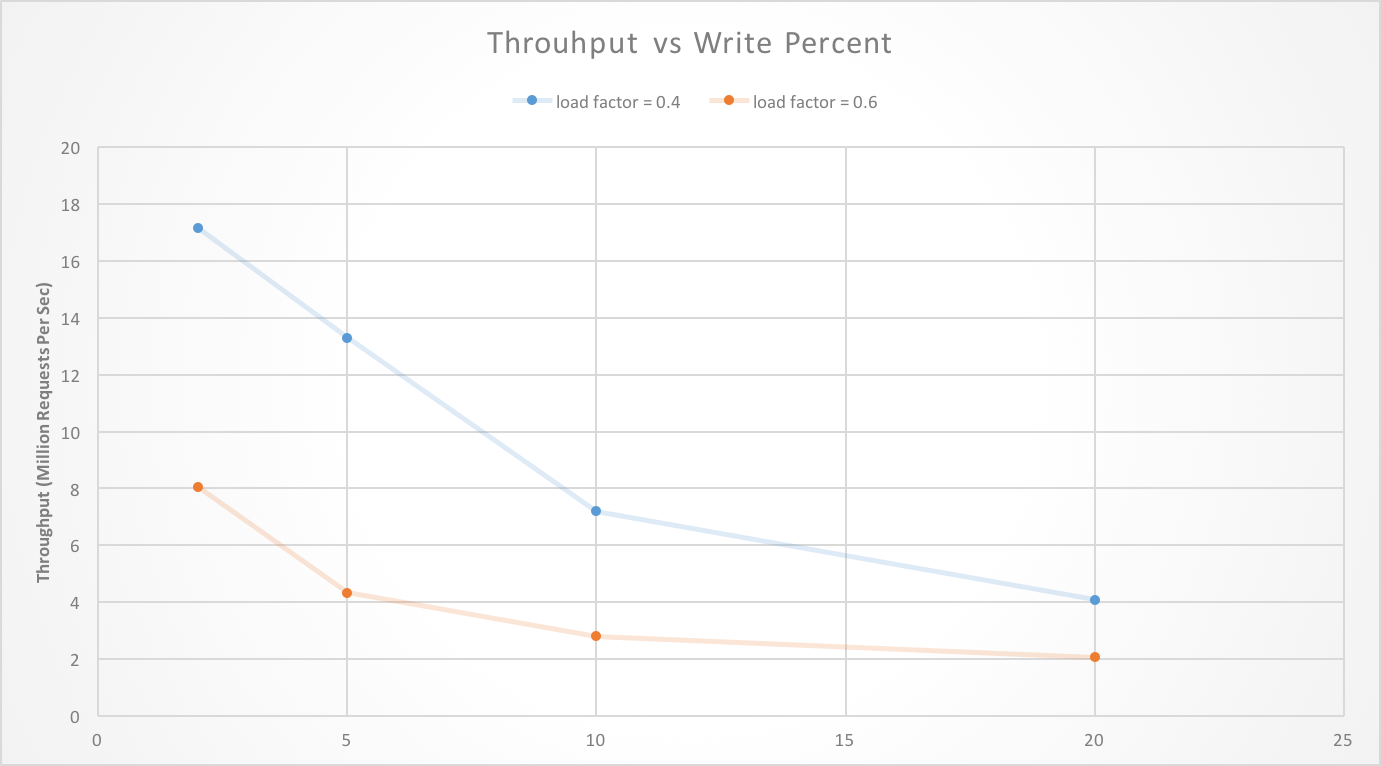

Analysis of Write Heavy Workload

As load factor increases, the length of cuckoo path to find an empty slot increases. Therefore, insertion time gradually increases on average, with increase in occupancy of hash table. As a result, overall throughput, i.e. requests per sec, decreases with increase in percentage of write request in load, as illustrated in figure. However, since the optimistic cuckoo hashing is targeted towards read heavy workload, this trade-off doesn’t hurt its performance goals.

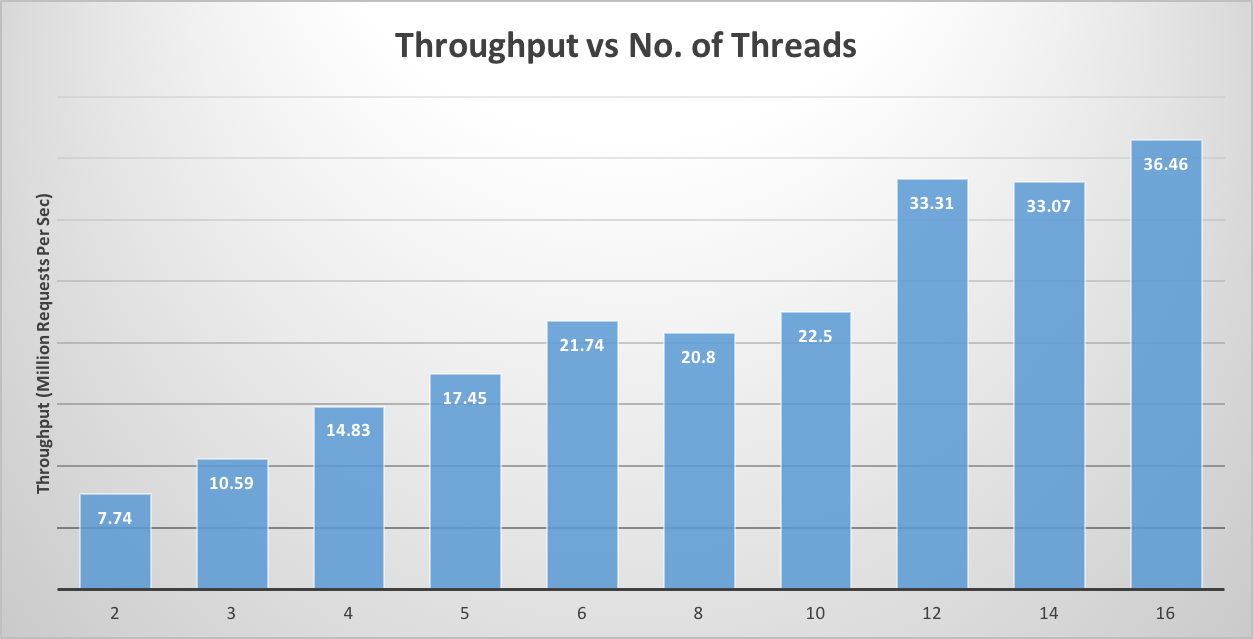

Scalability and Threads

As number of threads increases, throughput in case of both read-only and read-write workload increases. As there is no lock involved in optimistic cuckoo hashing, it doesn’t suffer from the issue of lock contention. In case of chaining based hash table with coarse grain and fine grain locking, throughput doesn’t increase with no. of threads. This is mainly because operations are serialized and there is significant issue of lock contention.

Comparison with Reference Paper

We incorporated improvements mentioned in MemC3 by Fan et al [1], and we were able to achieve similar performance numbers, as reported in paper. As mentioned in earlier section, we tested our implementation on similar configuration as mentioned in the reference paper.

Future Work

Multiple path search

In the search phase of insert, we can construct multiple cuckoo paths in parallel. At each step, multiple victim keys can be evicted and each key extends its own cukoo path. The search phase concludes when an empty slot it found in any of these paths. This has mainly two advantages : 1) Insert can find an emprty slot earlier, which ultimately improves the throughput. 2) Insert can succeed before exceeding maximum number of displacements.

Using SIMD for parallel lookups

In lookup phase, when each key maps to 8 slots, the use of SIMD semantics in OMP can help us check these 8 slots in parallel.

References

[1] https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~dga/papers/memc3-nsdi2013.pdf

[2] https://www.cs.princeton.edu/~mfreed/docs/cuckoo-eurosys14.pdf

[3] N. Gunther, S. Subramanyam, and S. Parvu. Hidden scalability gotchas in memcached and friends. In VELOCITY Web Performance and Operations Conference, June 2010

[4] B. Atikoglu, Y. Xu, E. Frachtenberg, S. Jiang, and M. Paleczny. Workload analysis of a large-scale key-value store. In Proceedings of the SIGMETRICS’12, 2012.

[5] R. Pagh and F. Rodler. Cuckoo hashing. Journal of Algorithms, 51(2):122–144, May 2004.

Work By Each Student

Equal work was performed by both project members.